As an avid backpacker and thru-hiker, I’ve spent the night outdoors in some pretty insane weather. From rain and snow to hail and lightning, I thought I’d seen it all. But the storm I experienced on the southern Appalachian Trail in August 2023 is one of the wildest things I’ve witnessed on trail.

The storm in this story caused flooding and destruction across the northern part of the North Carolina-Tennessee Border. It produced one confirmed tornado in Avery County, NC as well as other substantial wind damage. This was one scary night to be alone and outside! Luckily, I walked away unharmed and got a pretty crazy story out of it.

Sharing is caring:

The plan

It was mid-August, 2023. I was set to start an exciting 10-day solo section hike on the Appalachian Trail. The Appalachian Trail (AT) is a 2,190-mile continuous footpath from Georgia to Maine. On this trip, I planned to cover a 200-mile section of the AT between Carver’s Gap on the North Carolina-Tennessee border and I-77 in Virginia. This route includes the Roan Highlands, Grayson Highlands, and Chestnut Knob – some pretty incredible areas!

This region got hit with some nasty weather around the time I planned to start hiking. Consequently, I obsessively checked the weather forecast leading up to my trip. I even postponed starting by one day to wait out (what I thought was) the worst of the storms. After that, the forecast for my trip looked pretty okay: a moderate chance of rain for the first few days, with afternoon thunderstorms possible, followed by a week of sun. Not bad for the AT!

The start

I got dropped off at Carver’s Gap Sunday evening and hiked a short distance to Overmountain Shelter to tent camp. The next day, I set out to hike the 28 miles between Overmountain Shelter and Moreland Gap Shelter. Light rain started by mid-morning and slowly grew to a downpour. Around noon I reached Mountaineer Falls Shelter. I dove inside and took an extra long lunch break to avoid the worst rain.

After lunch, I reluctantly headed back out into the rain. The downpour eased to a drizzle then stopped altogether by late afternoon. Based on the forecast, I expected I was through the worst weather of my trip.

I arrived at Moreland Gap Shelter well before sunset. I felt pretty good and considered hiking a few more miles and tent camping instead. But ultimately, I chose to stay at the shelter. This choice may have saved my life, or at the very least, saved me from a much worse night.

The evening before the storm

Like many AT shelters, Moreland Gap Shelter is a three-sided lean-to. It is in a saddle between two small high points on a forested ridge. Saddles like this are bound to get blasted with some pretty serious wind from time to time. However, it wasn’t particularly cold or windy that evening, so I wasn’t concerned about sleeping in this location.

The sun set and no other hikers arrived. It looked like I’d be alone in the shelter. I knew from past trips that the southern AT is pretty empty this time of year. The northbound thru-hikers are long gone and the southbound thru-hikers haven’t arrived yet. Furthermore, many schools start in mid-August, so no summer break backpackers either. I usually don’t mind solitude in nature and even enjoy it. But this night for some reason, I felt a bit uneasy.

I hung my bear bag, laid my mat on the shelter floor, and got in my sleeping bag. I had cell reception so I checked the weather before I went to sleep. The forecast looked pretty good: cloudy overnight and then a moderate chance of rain starting in the morning. I settled in for a restful night.

The storm

Conditions change fast in the mountains.

I woke in the dark to roaring wind and water hitting my face. I was disoriented momentarily, then realized rain was coming into the shelter almost completely sideways! Wind and rain blasted through the saddle and straight into the open front of the three-sided shelter.

Even in my groggy state, my first instinct was to protect my down sleeping bag and puffy jacket from getting wet. Moving as fast as I could in my half-asleep state, I crammed them into my backpack. Hurriedly, I scanned the shelter floor for other non-waterproof items. My eyes landed on my phone, already coated in fat water beads.

As I shoved my phone into a Ziploc, a new alert flashed across my screen. I must have forgotten to set airplane mode before bed. It’s a National Weather Service warning for severe thunderstorms capable of producing tornadoes, followed by a list of counties along the North Carolina-Tennessee border. Not good.

Hastily, I secured the rest of my gear. I put on my rain jacket and flattened myself against the back wall of the shelter. Something was not right. I’d never experienced anything like this. The wind was driving sheets of rain into the shelter as the roaring noise grew louder and louder. I hunkered down and tried to stay calm.

Beneath the blaring roar, there was a second sound too – a strange rumbling. Horrified, I realized this was the near-continuous booming of tree after tree coming down. I wondered: will the shelter roof hold if something falls on it? There wasn’t much I could do other than stay put.

The damage

Fortunately, no trees fell on the shelter. I don’t have a good sense of how much time passed, but eventually, the roaring ceased. The wind died down enough that the rain stopped hitting me. Feeling relieved, I pulled my sleeping bag back out. Turned sideways against the back wall of the shelter, I managed a few hours of fitful sleep.

The next morning, as I started hiking, I quickly realized I would not be moving fast. Every few minutes, I encountered another freshly fallen tree, forcing me to stop and figure out the best way around, over, or through the jumbled branches. These fallen trees were annoying, but I had yet to see the real damage.

A few miles past the shelter, I reached a huge patch of blowdown crossing directly over the trail. I couldn’t simply walk around this, because every tree in a large patch of forest was uprooted and strewn across the ground. Furthermore, the ground was ripped up along with the tree roots in several places, leaving huge pits.

I ended up crawling and climbing through the blowdown patch like a jungle gym. I took these pictures as I made my way through. It’s hard to make out the actual trail in these photos with so many fallen trees. My pictures don’t come close to capturing the extent of the blowdown in this area.

Covered in scratches, I came out the other side of the blowdown patch. As I continued hiking, I reached a clearing and looked across a small valley to the next ridge over. On the opposite hillside, I saw another area of flattened forest, similar to the patch I crossed through. From this perspective, I could see it was not a patch, but a path: a short but distinctly elongated swath of destruction. Did a tornado touch down here?

I continued slowly making my way down the trail. There were no more big swaths of blowdown, just many, many individual fallen trees on the trail. I descended into a valley where rainwater was still running off the mountains. If it weren’t for the white blazes, I would have thought the AT was a creek!

I crossed Dennis Cove Road, where there were more fallen trees. The road itself was flooded with ankle-deep water in places. I forded the road and continued north, taking the high-water route above Laurel Falls towards Highway 321 (Hampton, TN). For the last mile before the highway, the trail and surrounding forest were one continuous ankle-deep wading pool.

Was it a tornado?

I can’t be 100% certain that the swaths of downed trees I saw were from a tornado. Later, I looked online for reports of a tornado near Dennis Cove Road in Carter County, TN on the night in question. In one article I found, the electric manager suggests “a tornado got in there and just bounced around for a while”, referring to the area above Dennis Cove Road where I spent the night of the storm. But in the same article, the reporter states that “no tornado was confirmed by the National Weather Service” for the area at that point.

Another article reports on “large swaths of forest that have been laid on the ground” near the Dennis Cove campground. I’m guessing that’s what I saw. This article also states that National Weather Service personnel came to “clear the area of debris and to determine whether a tornado had touched down in that area.” This article doesn’t say whether or not they found evidence of a tornado near Dennis Cove Road, but mentions a confirmed tornado touchdown in neighboring Avery County during the storm.

The tornado in Avery County was less than 10 miles as the crow flies from the Moreland Gap Shelter where I camped. This might explain the roaring I heard, but not the swaths of fallen trees along the AT between Moreland Gap Shelter and Dennis Cove Road.

Three days after the storm, I met a trail maintainer hiking along the AT near Watauga Lake. Coincidentally, this trail maintainer and his crew spent the previous day clearing the trail between Dennis Cove Road and Moreland Gap Shelter. He took out his phone to show me photos of his crew standing in front of the same blowdown swath I saw! The trail maintainer speculated that the swath may have resulted from a microburst rather than a tornado.

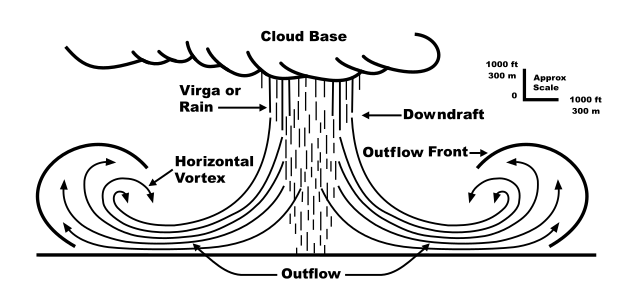

According to the National Weather Service, a microburst is a powerful downward draft of air under 2.5 miles across. They can produce winds up to 150 miles per hour and cause damage comparable to tornadoes.

Regardless of whether it was a tornado or a microburst, I’m certainly lucky to be unharmed. I think about how I seriously considered hiking a few more miles the evening before the storm. If I’d hiked further, I might have tent-camped directly in the path of destruction! I’m not sure why I decided not to hike further that evening, but I’ll always be thankful I didn’t.

The rest of my trip

I was pretty shaken up after the storm and seeing the extensive damage the next morning. I called my boyfriend’s mom, who was 45 minutes away and asked her to pick me up from the trail at Highway 321 (Hampton, TN). I’m glad I didn’t ask her to pick me up on Dennis Cove Road since she wouldn’t have gotten through due to the flooding and downed trees.

I spent a day and a half at my boyfriend’s parents’ house decompressing. Then, I got back on the trail and finished my section hike as planned. The rest of my trip was wonderful, with beautiful sunny days, cool nights, and not a single drop of rain! Though the night of the tornado was terrifying, I’m glad I didn’t let it ruin my whole trip or my love for backpacking.

Weather-Related Safety Tips for Backpackers

- Be prepared:

- Always tell someone where you are going.

- Check the forecast before you head out.

- Research the potential hazards and typical weather patterns of the area you are traveling in (e.g., afternoon thunderstorms, flash flooding, extreme heat, etc…).

- Pack rain gear and layers, even if you don’t think you’ll need them.

- While hiking:

- If possible, check the weather forecast throughout your trip. For AT hikers, the website ATweather.org provides forecasts for AT shelters.

- Plan to be off of exposed ridges and peaks well before storms arrive.

- Keep an eye on the sky so you can turn around and seek shelter if conditions deteriorate.

- If you hear thunder, turn around and seek shelter at once.

- Avoid narrow ravines and canyons during rain.

- In the event of a flash flood, seek higher ground immediately.

- At Camp:

- Avoid pitching your tent near standing dead trees that could fall on you.

- Camp above the high-water mark, away from riverbeds and low-lying areas, especially if rain is expected and when traveling in canyons that could flood quickly.

- During thunder and lightning:

- Avoid exposed ridges, peaks, and open fields.

- Seek shelter. An enclosed building or car is best, if available. If not, take cover in the forest but avoid tall features that stand out above the surroundings, such as tall, lone trees.

- Water conducts electricity, so avoid ponds and streams.

- Crouch, but don’t lie down. If you are with a group, spread out 100+ feet apart to decrease the chance that more than one person will be struck.

- During a tornado:

- Seek shelter immediately in a sturdy building, if possible. Otherwise, find a low-lying area and avoid trees that could fall on you. Lie down and protect your head from flying debris.

Have you ever experienced severe weather while backpacking or camping? What’s the scariest thing that has happened to you on trail? Join the conversation below!

Leave a comment